Fundamentals: What is Cloud-Optimized Scientific Data?

Why naively lifting scientific data to the cloud falls flat.

Scientific formats predate the cloud

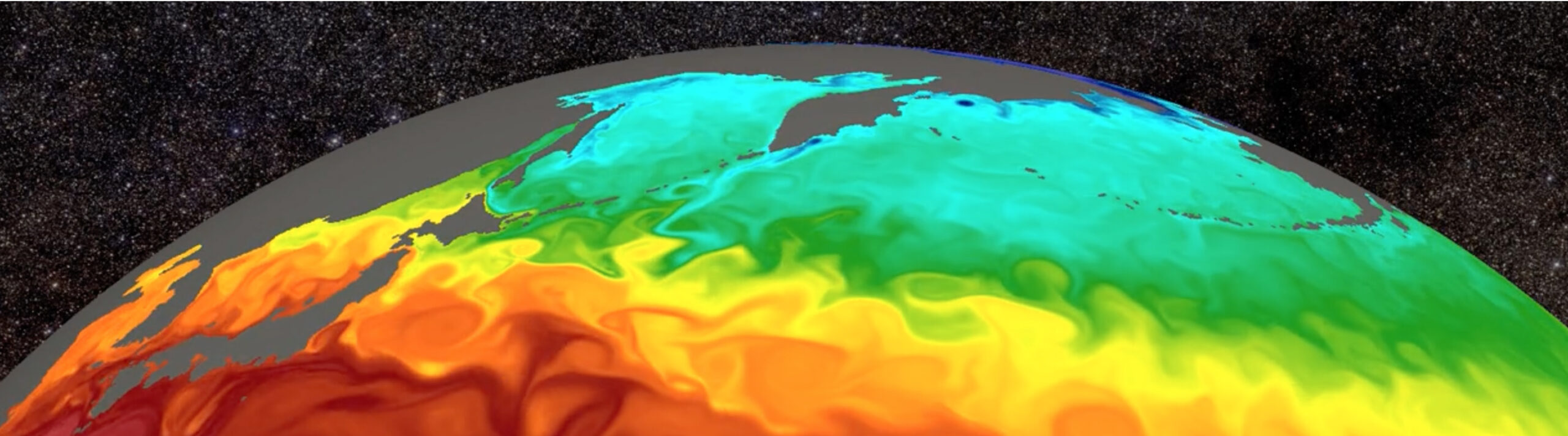

There are exabytes of scientific data out in the wild, with more being generated every year. At Earthmover we believe the best place for it to reside is in the cloud, in object storage. Cloud platforms are the state-of-the-art for managing tabular business data, and scientific data teams deserve similarly powerful tools. The Pangeo project has shown how the cloud can work for array data too, enabling efficient storage of enormous scientific datasets, scalable data-proximate compute, and sharing public data far and wide.

Unfortunately, most scientific array file formats (such as NetCDF, HDF5, TIFF, and GRIB) predate the cloud, so were never designed with access from cloud object storage in mind. We will demonstrate why naively moving netCDF files to the cloud results in deathly slow performance, and show you how Zarr, and other “cloud-optimized” data formats, solve this problem.

This post is for you if you’re responsible for managing an archive of scientific data and are curious about what a cloud migration would look like. It’s also for you if you’re just interested in learning more about how these formats work! If you’re not a developer or data engineer, you should still be able to follow along.

Object storage is not a filesystem

Cloud object storage (such as Amazon S3) and filesystems (like the one on your laptop) are both data storage systems, but are crucially different. We need to understand those differences to see why cloud-optimizing data is important.

Files are containers for data (each a series of bytes) that’s physically on your computer and managed by your Operating System. They are close at hand and fast to scan through. Imagine cooking in your own kitchen – you need to open the fridge to access ingredients (opening a file), it’s quick to look through what you have (fast to scan through the file), you need to put everything away and close the fridge door when you’re done (closing the file), and if someone else is blocking the fridge you have to wait until they are done (files are locked whilst another process edits them). This ingredient storage system is optimized for immediate use by one person at a time, to quickly examine a small number of close-at-hand items.

Object storage is similar in that each object is also a container for a series of bytes, but the way you access that data is different. There is no concept of “opening files”. Instead, all you can do is say “I would like to get this part of that object, please”, or “I would like to put some bytes into this location, please”. You interact with object storage only through these much simpler operations, such as GET, PUT, LIST, or DELETE, all sent over the network as HTTP requests.

Reading data from object storage is more like ordering ingredients directly from Costco. Instead of accessing ingredients directly, you submit specific orders (the GET requests). Each individual item takes time to deliver (called “latency”), but you can place many orders simultaneously, and the same distributor can fulfill orders for many customers at once. However, for this to work you need to know what is available and what you want to order in advance. This system is designed for scale rather than individual efficiency.

Lousy latency

The most important difference for this post is the “latency”, the delay between asking for a piece of data and receiving the first few bytes of that data. (Or between placing your Costco order and receiving it).

Latency with object storage is much higher than for a local filesystem. When you read a piece of data from part of a file sitting on your laptop, moving the pointer to the correct location in the file to begin reading the first few bytes into RAM takes ~1 millisecond. But to get a piece of data from object storage using a GET request takes a few 10’s of milliseconds from the moment you send the request over the network to the moment you receive the first byte back. Spoiler: this will be a problem.

Describe yourself in 8 bytes

Formats like netCDF are amazing because they are self-describing. The information required to understand the data in the file (known as the metadata) is present in the file itself, so you can simply read that one netCDF file to learn that it contains, for example, two arrays named “temperature” and “precipitation”, each of which is arranged as a 100x100x10 grid of 32-bit float values. Without this metadata you would either have had to know a priori what was in there, or just guess what it meant. Self-describing data formats were a major step forward for reproducible science and sanity in general.

But formats like netCDF/HDF5 are commonly sub-optimal for object storage because the descriptions of the contents are spread throughout the file. The tiny part that tells you that the first array is called “temperature” and the other tiny part that tells you that the second array is called “precipitation” are not adjacent; they are separated from one another by all of the thousands of actual temperature numeric data values. That means to find out a few kBs of information (all the metadata), you may have to comb through the entire file, which could be MBs or even GBs in size. Imagine if you had to walk through the entire Costco store just to find out what departments they have.

Death by a thousand GETs

Presented with a URL pointing to a mystery file sitting in object storage, you must begin by issuing one GET request for the first few bytes (called the “magic” bytes), and wait for that to come back to learn that this is, in fact, a netCDF file. Then you can issue another GET request for some other set of bytes to learn that this file contains an array called “temperature” of size 1GB. Only once that comes back do you know how many bytes to jump forward for another GET request to learn that the next array is called “precipitation”.

This is not a problem for a local filesystem. Your pointer starts at the start of the file, and using the filesystem’s seek operation to move it to a new location is very speedy (~0.1 milliseconds on an SSD), so scanning through the entire file by moving the pointer forwards lots of times in a row is no big deal.

But to read a lone netCDF file in object storage you have to issue many GET requests, one after another, each of which adds another round-trip’s worth of latency. As we learned above, latency for object storage is very high, so this rapidly adds up.

Let’s demonstrate. This demo shows what happens when you naively try to open a 1GB (3GB uncompressed) netCDF file in a public S3 bucket using Xarray, and print all the metadata you might care about (e.g. array names and sizes), by reading it as if it were a local file. Each filesystem read call is translated into one HTTP GET request, with no special treatment like caching or pre-fetching.

As expected, the performance is atrocious – it takes the better part of a minute just to read the metadata, making 502 separate GET requests just to download a grand total of 267KB. That’s an effective bandwidth of only 7 KB/s, far slower than even 1990’s-era dial-up internet.

(Note there are many ways this could be optimized, such as by caching, pre-fetching, or repacking metadata. Even using the netCDF4-python library out-of-the-box would perform somewhat better. But the point is that if you do not or cannot alter the files, and you naively treat object storage as if it’s a local filesystem, you will get abysmal performance.)

You could instead ask to download the entire file up front, which means downloading all the data when you really only wanted to see the metadata to know what’s inside. But then you are downloading millions or billions of times more data than you know you will need.

Even worse – this is all for one file. Most datasets of interest consist of thousands of netCDF files, making these problems a thousand times worse! It can potentially take hours just to open such a dataset on the cloud. This sucks, and is ultimately all a consequence of the data not being “cloud-optimized”.

A series of fat pipes

At this point you are probably wondering, “if the latency of the cloud is so high then what is so good about it?” The answer is that what object storage lacks in latency it more than makes up for in throughput.

If the internet is famously “a series of tubes”, then the cloud is a series of fat pipes. Inside a data center, the object storage is connected to the compute resources via connections of enormous bandwidth. Whilst it might take a moment between you asking for the tap to be turned on and water starting to flow, once it begins you will quickly be drenched by a massive firehose of data coming through that fat pipe.

The total amount of data transferred divided by the total time it took to transfer it is called throughput. The throughput of object storage can be through the roof – the PyWren paper demonstrated linear scaling to aggregate read throughputs of 80GB/s on S3, with no signs of slowing at even larger scales. This kind of performance is comparable to that of the expensive filesystems of top supercomputers, but on far cheaper commodity hardware instead of specialized HPC hardware, and available to anyone.

How do we achieve this massive throughput? The problem we saw with the metadata is not that we’re doing a lot of GET operations – the cloud is actually great at that – it’s rather that we’re doing all those GETs sequentially, one after the other. If we only needed to issue one GET request we would only have to wait once, and if we were able to somehow immediately issue all the GET requests we were ever going to need, the power of object storage is that it can send all the results back to us simultaneously, thereby taking full advantage of the fat pipe. (In the Costco analogy, you could submit an order for a literal truckload of apples.)

Idea: Separate the metadata

So to benefit from object storage, traditional netCDF isn’t going to work – we have to change something. The first problem to solve is needing to do all those sequential GETs just to retrieve a very small amount of metadata.

If that metadata were instead separated out into a known location (for example, a separate accompanying “sidecar” file), we could simply issue one GET request for the entire contents of that small metadata file. Then we would know everything about the structure of the rest of the data after just one round trip’s worth of latency, which is the fastest we could possibly have learnt about anything in object storage. (Costco now has a catalog.)

Separating the metadata from the data is also what allows scalability – more data no longer implies searching for longer to find the metadata, as it’s always separated into a known location.

Idea: Split the data into chunks

Once we know what’s in the dataset, the other problem is how to get only the parts of the data we actually want, while taking advantage of the massive throughput object storage offers.

If we split each data array into many small chunks, then we can download only the subset of data we actually want to use. For example, all chunks that make up the most recent satellite image of a certain location. If each chunk is a separate file, then we can easily request them independently and in parallel, potentially all at once through our fat pipe.

(If you’re really paying attention you might ask: “If small is good why don’t we just make the chunks as small as possible?” One reason is that we also want to compress each chunk to save storage space. There is a trade-off between larger chunks, which compress more efficiently, and smaller chunks, which allow you to make more targeted requests.)

NetCDF and HDF5 already use chunking internally within their file formats. However, the information about the chunks (another form of metadata) is relatively slow to access on object storage, for the reasons described above, meaning that it isn’t trivial to just grab the chunks we want. You also need to split the chunks out if you want to partially update an existing dataset in the cloud, because object storage doesn’t allow you to edit files, only replace them in their entirety.

Congratulations! That’s Zarr.

So let’s invent a new file format designed to work beautifully with object storage, with separate files for the metadata and splitting the data into chunks. Oh wait – that already exists: it’s called Zarr.

This isn’t facetious – Zarr really is faster because of these two main reasons. In fact, you can clearly see it in this diagram of the internal structure of an example Zarr store.

All the metadata for a particular array are in one zarr.json file, which can be retrieved with a single GET request. The actual data arrays are split into grids of chunk files, any set of which can be retrieved simultaneously using one GET request per chunk.

Back in 2018, there were various ideas for overcoming cloud latency, but it’s cloud-optimized formats such as Zarr, Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (a.k.a. COG), and even cloud-optimized HDF5 that have taken off within climate, weather, microscopy, and other scientific data communities.

Note that none of these ideas were invented by Zarr. Commercial cloud object storage is almost 20 years old(!) and cloud-optimized tabular formats such as Avro and Parquet were developed to take full advantage soon afterwards. (Parquet was a direct inspiration for Zarr.) To understand why we can’t just use tabular formats for scientific data read our recent fundamentals post on tensors vs tables.

Consolidating power metadata

However, this still isn’t perfect. Zarr’s native format on object storage stores metadata for each array in a dedicated file, i.e. it has one zarr.json file to go get per array. Some datasets have hundreds of different arrays, so it would be considerably more efficient still if all the metadata for all the arrays were somehow in one json file.

That’s what Zarr’s “consolidated metadata” feature is: one weird trick to minimize the number of GET requests, by consolidating all the metadata into one zarr.json file at the root of the Zarr store. Consolidated metadata is arguably a bit of a hack, but because Xarray actually writes this by default, many existing Zarr stores have it already.

Icechunk: Consolidated metadata + version control

Earthmover’s open-source format Icechunk takes consolidated metadata and runs with it. Like a conventional Zarr store, Icechunk also stores all the metadata and chunks as separate objects, but Icechunk also has a system for tracking version history of all those objects, providing git-like version-control features for your data. You can think of it as tracking successive versions of consolidated metadata, each of which describes the state of your entire Zarr store at one point in its history. For more details, read the Icechunk launch blog post, or watch the webinar on version control with icechunk.

As the metadata is always consolidated, Icechunk also minimizes the number of GET requests required to open the dataset. We ran a simple benchmark to confirm this.

xarray.open_dataset on a single file (1GB compressed, 3GB uncompressed) of NOAA GFS data, stored in different formats. Code was run from a laptop in New York, so the time reflects latency to reach the data in AWS us-east-1. Code to reproduce the results is available on Github.Our benchmark compares the number of HTTP requests issued, and the overall time taken to call xarray.open_dataset on 1GB’s worth of array data stored in S3. It includes the netCDF demo from earlier, compared against the same data stored as native Zarr, Zarr with consolidated metadata, and as icechunk.

While Zarr with consolidated metadata minimizes the number of HTTP GET requests required overall, Icechunk has similar speed advantages, and all the power of transactions and version control!

(For the more technical amongst you see the footnotes about this benchmark at the end of the article.)

High throughput means low cost

That’s latency. For throughput, thanks to optimizations in Zarr-Python 3 and Icechunk, our open-source software stack is now approaching the theoretical limits of maximum possible throughput. So when streaming data from object storage to cloud compute within the same datacentre, you can use the full bandwidth of those fat pipes.

This translates to big cost savings. Multi-dimensional data analysis workloads are often IO-bound, meaning that the CPUs you’re paying for spend most of their time waiting for data to come in, not actually computing on it. So the 100x speedup we see for NASA data using Zarr and Icechunk compared to using non-cloud-optimized netCDF translates to 100x less time you’re paying for CPUs to sit around, and so 100x lower cloud computing bills!

No free lunch

Whilst using cloud-optimized data in the cloud is generally a no-brainer, there are some downsides to the cloud approach.

Object storage always has high time-to-first-byte. If reacting to new data as fast as physically possible really matters to you (e.g., because you’re doing high-frequency trading), then you should not use object storage at all. High-frequency trading is an example of a “transactional” workload because the objective is to make a decision and write a small amount of information back as fast as possible (to make the trade). Object storage is better suited for “analytical” workloads, in which a larger amount of data is ingested for important but not subsecond-urgent querying. These analytical workloads are plenty common within scientific and geospatial domains.

Using a new file format generally requires copying the original data. That requires both more storage space to hold the copy as well as compute to perform the copying. But what if we didn’t have to copy all the data? Look out for a future blog post about “Virtual Zarr”…

Towards the great scientific supercomputer in the sky

Hopefully now next time you hear “cloud-optimized data” you will understand that it’s really just about separating the metadata from the chunks, and fetching things efficiently.

But our vision for working with scientific data in the cloud requires more than just cloud-optimizing files and dumping them into cloud buckets. Ideally we want to forget about files entirely and just live in a world of seamless cloud data lakes. But that will have to wait until next time!

Footnotes

- When Ryan and Joe first integrated Zarr with Xarray in 2017, it wasn’t even possible to open netCDF in the cloud directly without downloading the entire file.

- Recent improvements to opening netCDF directly, such as “cloud-optimized HDF5”, are using these same ideas, and so are formats such as COG and Parquet.

- Zarr’s performance on this chart used to be a lot worse – big improvements were made to the Zarr-Python library by the open-source community.

- The reason the number of requests and total time don’t just scale in lockstep is because if you issue a lot of requests all at once it only takes one round-trip’s worth of latency to get them all back. That’s basically what Zarr without consolidated metadata is doing.

- For a larger subset of GFS containing more files, netCDF would take even longer as the metadata of every file would need to be read, while Zarr and Icechunk would require approximately the same amount of time. So Zarr & Icechunk are the only options here that can scale to accessing truly massive datasets.